A number of key issues followed Governor Berkeley back into Virginia after his 1662 visit to England. He was to enforce the Navigation Acts, build new towns, and enact new taxes. Arguably, however, an issue had been brewing in the Old Dominion for some time before he returned to power – slavery.

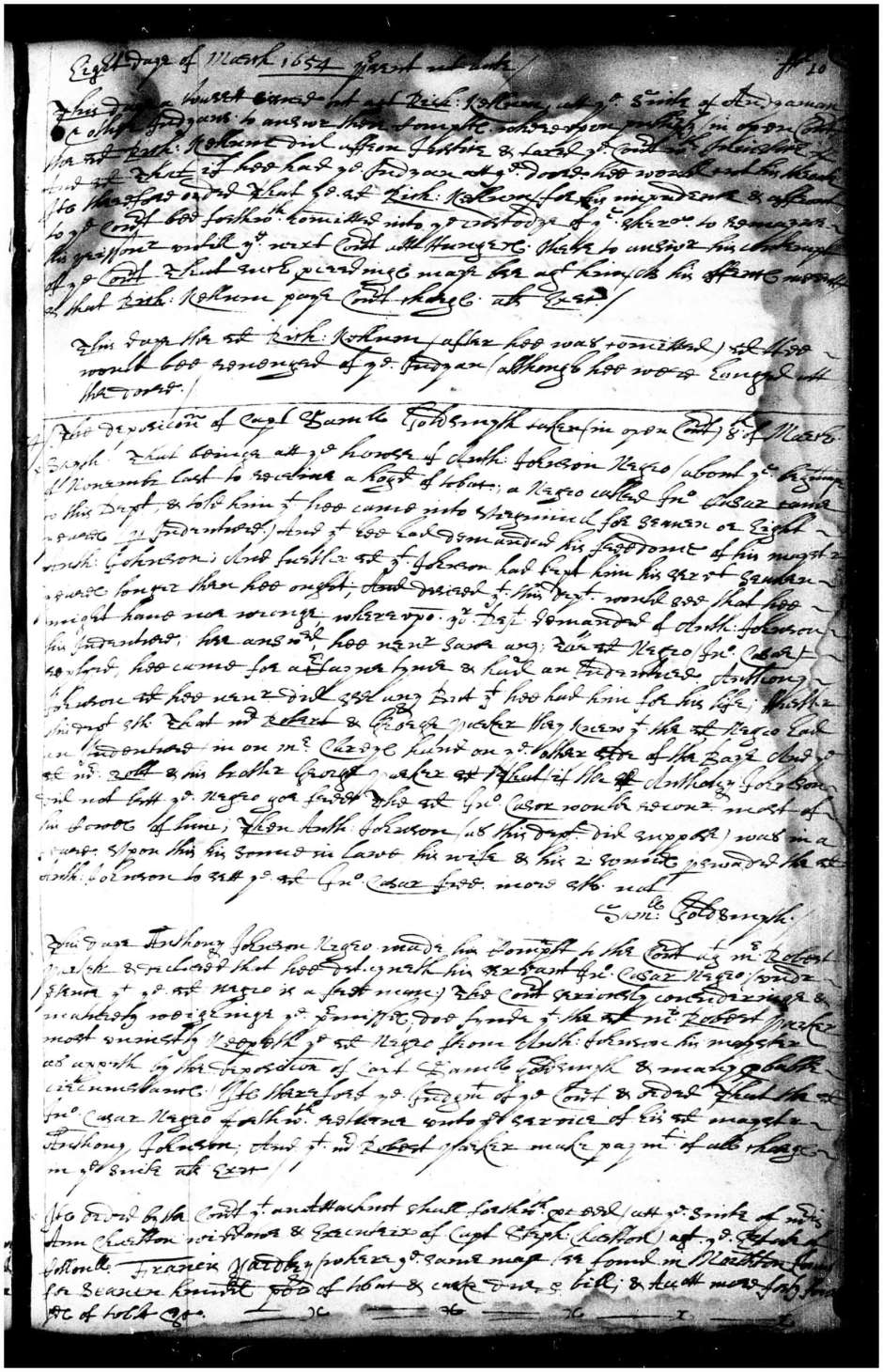

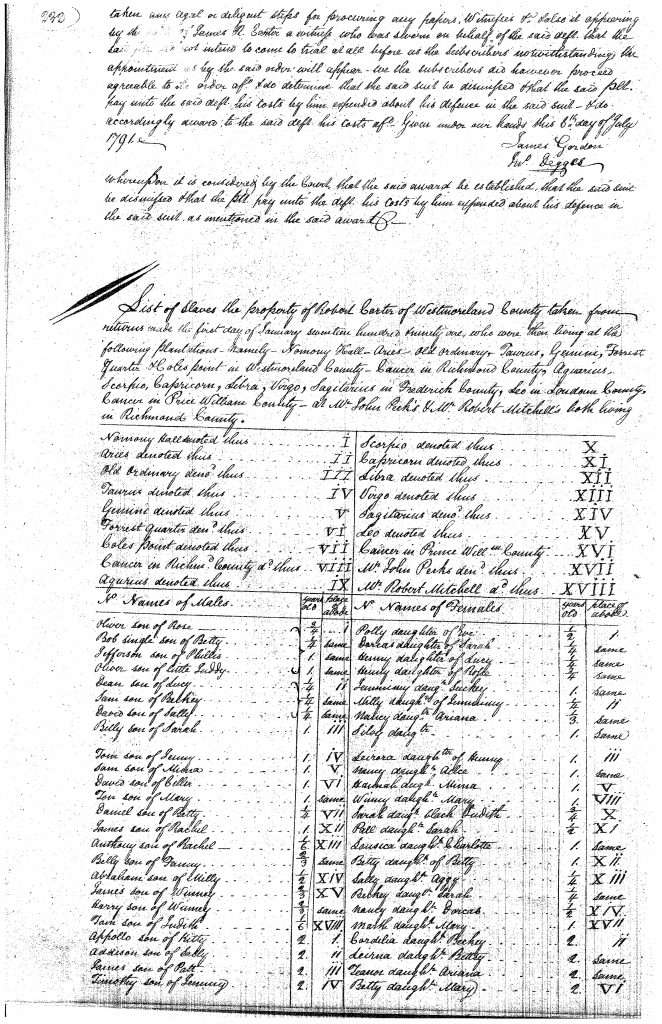

Slavery had not been codified legally, though it had existed in many forms for decades. Two important court cases set the Commonwealth on the pathway toward eventual chattel slavery in 1705. The first case involved Antony Johnson, who’s servant, John Casor, had fled Johnson’s Eastern Shore plantation. Johnson sued Casor, and Casor’s protector. Casor lost, and was ordered to return to Johnson’s control in perpetuity. In all of Virginia’s remaining records, this was the first mention of the term slavery.

The second case, which involved one Elizabeth Key, served to help define who could be considered a slave from birth. Key ultimately won her case, but the laws serving to free her were changed thereafter and soon harmed future generations for centuries.

LINKS TO THE PODCAST:

SOURCES:

- Billings, Warren M.; Selby, John E.; and Tate, Thad W. Colonial Virginia: A History. White Plains, NY: KTO Press. 1986.

- Billings, Warren M. Sir William Berkeley and the Forging of Colonial Virginia. Baton Rouge, LA: LSU Press, 2004.

- Billings, Warren. A Little Parliament: The Virginia General Assembly in the Seventeenth Century. Richmond, VA: Library of Virginia, 2004.

- Breen, T.H. and Innes, Stephen. Myne Owne Ground: Race & Freedom on Virginia’s Eastern Shore, 1640-1676. New York: Oxford University Press, 1980.

- Craven, Wesley Frank. White, Red, and Black: The Seventeenth Century Virginian. Charlottesville, VA: University of Virginia Press, 1977.

- Craven, Wesley Frank. The Southern Colonies in the Seventeenth Century: 1607-1689. LSU Press, 1949.

- Dabney, Virginius. Virginia: The New Dominion, A History from 1607 to the Present. Charlottesville, VA: University of Virginia Press, 1971.

- Genovese, Eugene. Roll, Jordan, Roll: The World the Slaves Made. New York: Vintage, 1976.

- Horn, James. Adapting to A New World: English Society in the Seventeenth-Century Chesapeake. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1994.

- Mapp, Alfred J. Virginia Experiment: The Old Dominion’s Role in the Making of America, 1607-1781. Lincoln, NE: iUniverse, Inc., 2006.

- Neill, Edward D. Virginia Carolorum: The Colony under the Rule of Charles The First and Second, A.D. 1625-A.D. 1685. Albany, NY: Joel Munsell’s and Sons, 1886.

- Rothbard, Murray N. Conceived in Liberty. Auburn, AL: Ludwig Von Mises Institute, 1999.

- Tyler, Lyon Gardiner. The Cradle of the Republic: Jamestown and the James River. Richmond, VA: The Hermitage Press, 1906.

- Wallenstein, Peter. Cradle of America: Four Centuries of Virginia History. Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas, 2007.

- Walsh, Lorena S. Motives of Honor, Pleasure, and Profit: Plantation Management in the Colonial Chesapeake, 1607-1763. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2010.

- Washburn, Wilcomb E. Virginia Under Charles I and Cromwell 1625-1660. Kindle Edition.

- Wertenbaker, Thomas Jefferson. Virginia Under the Stuarts: 1607-1688. New York: Russell and Russell, 1959.

- Wertenbaker, Thomas Jefferson. The Planters of Colonial Virginia. Kindle Edition.

- Wise, Jennings Cropper. Ye Kingdom Of Accawmacke: Or The Eastern Shore Of Virginia In The Seventeenth Century. Richmond, VA: The Bell Book and Stationary, CO. 1911.

- The Navigation Act of 1651 (Act passed by Rump Parliament and spurned by Berkeley).

- The Navigation Act of 1660 (This is the Act that concerned Virginians before Charles II’s Restoration).

- The Navigation Act of 1663 (Argued previous to July 1663 ratification, after Berkeley had returned to Virginia).

All photography used on this site is owned and copyrighted by the author unless otherwise noted. The featured image is of “Court Ruling on Anthony Johnson and His Servant” found in the Northampton County Deeds, Wills, Etc., March 8, 1654/5, 7 (1655–1668), fol. 10 – from the Encyclopedia Virginia.

Music used for this episode – Louis Armstrong and the Mills Brothers,”Carry Me Back to Old Virginia” available on Apple Music, and “Hurricane” by Needtobreathe also available on Apple Music.